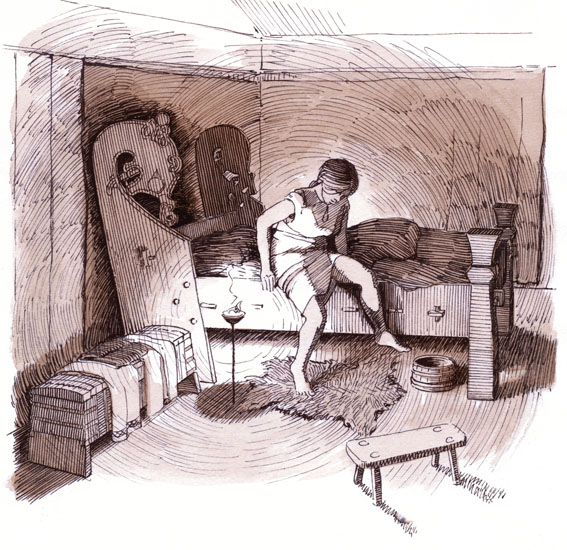

An example of Old Norse beds and bedding

In response to the growing number of questions about how early medieval people slept and what means they used for quality sleep, I decided to write an overview article that would bring the issue closer to the English reader. For research, we can use both the archaeological finds (very rich graves) and written references from Family sagas, which deal with both ordinary people and leaders. If we combine these sources, we get a relatively complete picture, which is – despite some differences – in many ways similar to the recent state.

An ordinary person

In early medieval Scandinavia, people commonly slept naked or dressed in linen underwear (Short 2010: 115), which seems to be a practice known on the Continent as well (Thietmar of Merseburg : Chronicle V:6). The written sources also clearly show us that husband and wife slept together in the same bed, and if they did not, it indicated problems that could be grounds for divorce (e.g. Rígsþula; Gísla saga 9, 16, 17, 26). In Old Norse, a bed was referred to as a beðr, hvíla, rekkja or sæng. It is believed that breakfast took place around seven o’clock in the morning, when everyone was already on their feet; from some indirect notes from Family sagas, it seems that it was common to go to bed before midnight. It is therefore likely that the circadian biological rhythm was aligned with the rhythm of day and night. Of course, even among the early medieval Europeans we would find “larks” and “owls”: the workers of Skallagrímr do not like that their master forces them to work at the forge from the early hours of the morning, to which Skallagrímr replies that those who want to earn must start work soon (Egils saga Skallagrímssonar 30).

Almost no archeologically detected houses had extensions for individuals or couples – such lockable bedrooms (lokrekkja, lokhvíla) are known only in some preserved hall buildings (e.g. Stöng) and in sagas, where they are reserved for a prominent couple of a householder and a housewife (Vidal 2013: 57-58). Most of the inhabitants of the house slept, depending on the available options, on the ground by the fire or on a raised wooden step (set), on a bench (bekkr) or in the attic (lopt), i.e. in a public space (Foote – Wilson 1990: 160; Graham-Campbell 1980: 10; Short 2010: 91). Smoke and darkness completed the scene. How well it was possible to heat the house is a question, but we will certainly not be far from the truth if we say that such more or less improvised beds most likely consisted of a straw mattress, a simple pillow, wool blankets or furs. It is also possible to speculate about special buildings in which the workers slept (svefnhús), however, it must be noted that such mentions are rare and in most Family sagas the workers sleeps on steps placed on the sides of the hall (skáli). Whether the beds could have taken the form of mobile wooden structures that would have been stored in the attic during the day, we know nothing at all, and such a possibility does not seem very likely.

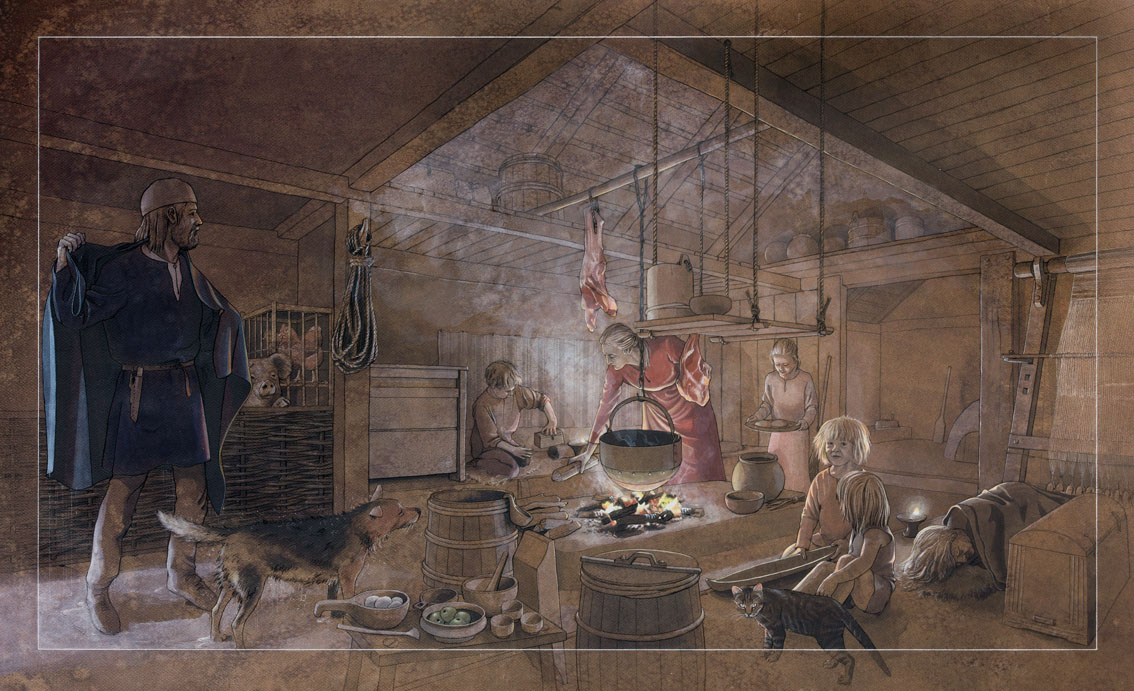

Drawn reconstruction of the interior of a building in Haithabu.

Source: Flemming Bau, Schietzel 2022: 278-9.

Plans of some types of Scandinavian houses.

Top: house of Haithabu (Schietzel 1981: 45, Abb. 21).

Middle: house from Aggersborg (Roesdahl – Sindbæk 2014: 55, Fig. 3.5).

Bottom: house from Stöng (Foote – Wilson 1990: 156).

A rich person

When we described the rather improvised sleeping of the workers, we can now see how the landlords and their rulers slept. If the houses had adjacent bedrooms, they were very small rooms – for illustration, we can cite the extension from Stöng, which is roughly 1.5 × 1.5 m (Short 2010: 91). The beds that have survived are not much larger. At least three animal-headed beds and at least three less massive beds were probably deposited in Oseberg (Grieg 1928: 81-105), while at Gokstad fragments of five beds were found, two of which are complete enough to be reconstructed (Nicolaysen 1882: 42). The bed from Pskov is about 2.2 m long and about 1.1 m wide (Jakovleva 2016: 133).

Basic overview of some 9th-10th century beds.

Copies of beds from Oseberg and Gokstad. Source: Grieg 1928: Fig. 40, 42, 43, 51.

Bed model from chamber grave 3 from Pskov. Source: Jakovleva 2016: 133.

The interior spaces of some of the beds are so short that it raises the question of whether the beds were intended for sleep in a seated position. This would also be indicated by the small dimensions of the bedrooms and some written references (e.g. about the death of Unnr in Laxdæla saga 7). Such a position could probably be related to the majesty even during sleep. One of the iconographic sources depicts this exact method (Paulsen 1992: 50). In contrast, however, there were necessarily beds that were longer and allowed full extension (see Brownlee 2022; Paulsen 1992: 43-51).

It was standard for wooden beds to be softened with straw mattress (hálmr). Thus, in Gísla saga (26) we can read how Refr and his wife hid Gísli from the pursuers in a straw mattress in their bed after removing the bedding (fǫt) from it. Of course, this standard was not enough for very rich people, so the straw mattress was replaced by a more luxurious down and feather mattress (dýna). This is evidenced by the 31.268 kg of down found in Oseberg (Vedeler 2014: 290), which were apparently sewn into fabric of plant origin; there are even visible signs of laying on the fragments (Ingstad 2006: 227–229). Eyrbyggja saga (50) corresponds to this unique find, which tells of Þórgunna, who brought a chest of imported bedding to Iceland from overseas: „When she arrived at the homestead, she asked where her bed would be, and when she was appointed place, she unlocked the chest and took out the richly embroidered bedding, and spread English sheets and silken blankets over the bed. She also took out the bed canopy with all the curtains. It was such a fine piece of equipment that no one had seen before.“ When the peasant Þuríðr, who envied her this equipment, asked her about the price, Þórgunna replied thus: „I will not sleep on straw because of you.“

Depiction of beds in 9th-10th century iconography.

Source: Brownlee 2022: Fig. 2; Paulsen 1992: 44, 49-50.

We know next to nothing about coverings (hvítill, kult, kǫgurr) and sheets (blæja). We can assume that they were made of different materials and there were differences in quality. A woolen textile was also found in Oseberg, which may have been a covering with down hidden inside (Ingstad 2006: 227-229). Information about silk blankets and English linen sheets can be gathered from the passage on Þórgunna mentioned above. We can well imagine that linen was an ideal material for the production of sheets. As for the pillows (hægindi), we know of at least two archaeological finds from the 10th century and others that are older. At the same time, pillows are mentioned in Family sagas. Both pillows we have available are made of wool and stuffed with bird feathers. One of them was preserved in a rich grave from Mammen and measures 78 × 28 cm (Østergård 1991: 136), the other was found in Øksnes in Northern Norway, measures 30 × 30 × 4 cm and is stuffed with eider, cormorant and gull feathers (Dove – Wickler 2016). For comparison, we can mention the contents of the pillow from grave Valsgärde 7, in which the remains of feathers from goose, wild duck, eider, corvid, tufted duck, eagle-owl and others were found (Berglund – Rosvold 2021: 229).

Analyzes of used feathers are very rare. It is generally believed that down-filled textiles is a sign of high status. At the moment, I know of only six Norwegian (Oseberg, Gokstad, Grønhaug, Haugen i Rolvsøy, Søndre Moksnes, Øksnes) and three Danish sites (Mammen, Hvilehøj, Køstrup) from the Viking Age where feathers used in bedding were found, and some of them are among the most significant graves we know. In literature, feathers appear as a sign of luxury (Ingstad 2006: 227). For example, the sorceress in the Eiríks saga rauða (4) must be seated on a pillow stuffed with chicken feathers. According to the Haraldskvæði (6), Harald Fairhair in his youth wore mittens stuffed with down, and after her death, Harald’s wife was put to the grave „sitting on down“ [pillow filled with down] (Haralds saga hárfagra 26). At the same time, feathers or products containing them appear as a form of collecting taxes and booty (Óhthere and Wulfstán; Foote – Wilson 1990: 160), from which we conclude that it was also a valuable trade item. Nevertheless, feather quality was graded, both by coarseness (quills [fiðri] × down [dúnn]) and origin. Goose and chicken feathers were the lowest, and seabird feathers could be higher. The highest price was the down of the sea eider (æðardúnn), which is still an extremely expensive commodity, valued for its unique heating properties. It seems that the Scandinavian graves containing feathers always contain a certain amount of eider down.

It is important to note that the bed was given great importance. It was kept clean, which could be taken care of by both the servants and the housekeeper herself.

Drawn reconstruction of a bed from Oseberg. Zdroj: Flemming Bau.

A man on the move

If people were traveling, they had to partially compromise their demands, but they still counted on a quality overnight stay. First of all, the journey, if it was not long, was planned so that the traveler was constantly staying in houses. It was customary for a guest to have food, drink, conversation and then a place to sleep. Regular passengers could sleep in the same building as the local workers, or in the barns and quarters. Egill from Egils saga Skallagrímsonar during his visits to Norway sleeps in workers quarters (eldahús; ch. 43), in which there is plenty of straw, and in a barn together with horses (kornhlaða, ch. 71). In the towns, it was apparently possible to rent an entire building that would fit, for example, a ship’s crew (Þorsteins saga hvíta 4), similar to pilgrim houses on the Continent. We cannot say where the rare visitors were placed, but we can assume for sure that especially the rich landowners were prepared for these eventualities.

If traveling by ship, it was either possible to anchor for the night regularly (if the nature of the journey allowed, e.g. Egils saga Skallagrímsonar 49) or to sleep directly on board. On sea voyages, one slept under sail in leather sleeping bags (húðfat); for example, in Landnámabók, a certain boy sleeps on a ship in a sealskin. Wealthy ship owners could take folding tents and beds on board, as we can see in the examples from Gokstad and Oseberg.

If a person got into a difficult situation and had to wait in nature, she or he used all available means. It was a common thing that if one traveled to certain places on a regular basis (meetings and assemblies), stone foundations (called búðir) were built on the spot, so that this structure could be covered with a canvas during each visits. The same is shown in the case where people lost their homes and had to improvise quickly. Shorter-term stays could be solved with natural shelters, tents and canvases. An ordinary person could use a sleeping bag, fur, woolen cloaks, blankets, and the like while traveling, or use local insulation resources. In the Njáls saga (153) we find a passage in which the shipwrecked crew collects moss for covering themselves during the sleep. Caves could also serve as temporary shelters (Bergsvik 2018).

Bibliography

Sources

Egils saga Skallagrímssonar = Saga o Egilovi, synu Skallagrímově. Trans. Karel Vrátný, Praha 1926.

Eiríks saga rauða = Eiríks saga rauða. Ed. Einar Ól. Sveinsson & Matthías Þórðarson, Íslenzk fornrit IV, Reykjavík 1935. Translated to Czech as: Sága o Eiríkovi Zrzavém. Trans. L. Heger. In: Staroislandské ságy, Praha 1965, 15–34.

Eyrbyggja saga = Eyrbyggja saga. Ed. Einar Ól. Sveinsson & Matthías Þórðarson, Íslenzk fornrit IV, Reykjavík 1935. Translated to Czech as: Sága o lidech z Eyru. Trans. L. Heger. In: Staroislandské ságy, Praha 1965: 35–131.

Gísla saga = Sága o Gíslim. Trans. Ladislav Heger. In: Staroislandské ságy, Praha 1965, 133–185.

Haralds saga hárfagra = Haralds saga hins hárfagra. Ed. Nils Lider, H. A. Haggson. In: Heimskringla Snorra Sturlusonar I, Uppsala 1870.

Landnámabók = Landnamabók I-III: Hauksbók, Sturlubók, Melabók. Ed. Finnur Jónsson, København 1900.

Laxdæla saga = Sága o lidech z Lososího údolí. Trans. Ladislav Heger. In: Staroislandské ságy, Praha 2015, 213–362.

Njáls saga = Sága o Njálovi. Trans. Ladislav Heger. In: Staroislandské ságy, Praha 1965, 321–559.

Óhthere and Wulfstán = Plavby Óhthera a Wulfstána. Trans. Klára Petříková. In: Čermák, Jan (ed.). Jako když dvoranou proletí pták, Praha 2009, s. 540–545.

Rígsþula = Píseň o Rígovi. Trans. Ladislav Heger. In: Edda, Praha 1962, 169–181.

Thietmar of Merseburg : Chronicle = Dětmar z Merseburku: Kronika. Trans. Bořek Neškudla, Jakub Žytek, Martin Wihoda, Jiří Ohlídal, Praha 2008.

Þorsteins saga hvíta = Þorsteins saga hvíta. Ed. Jón Jóhannesson. In: Íslenzk fornrit, 11. Austfirðinga sögur, Reykjavík 1950.

Þorbjǫrn hornklofi : Haraldskvæði = Þorbjǫrn hornklofi : Haraldskvæði (Hrafnsmál). Ed. R. D. Fulk. In: Skaldic poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages. Vol. 1, [Poetry from the kings’ sagas 1 : from mythical times to c. 1035], ed. Diana Whaley, Turnhout 2012, 91–117.

Literature

Berglund, Birgitta – Rosvold, Jørgen (2021). Undersökning av fjädrar från båtgravar i Valsgärde Gravbacke. In: Fornvännen 116, 327-332.

Bergsvik, K. A. (2018). The perception and use of caves and rockshelters in Late Iron Age and medieval western Norway, c. AD 550–1550. In. Bergsvik, K. A. – Dowd, M. (eds.). Caves and Ritual in Medieval Europe, AD 500–1500, Oxford – Philadelphia, 32-62.

Brownlee, Emma (2022). Bed Burials in Early Medieval Europe. In: Medieval Archaeology 66:1, 1-29.

Dove, C. J. – Wickler, Stephan (2016). Identification of Bird Species Used to Make a Viking Age Feather Pillow. In. Arctic, Vol. 69/1, 29–36.

Foote, Peter – Wilson, David M. (1990). The Viking Achievement, Bath.

Graham-Campbell, James (1980). Viking Artefacts: A Select Catalogue, London.

Grieg, Sigurd (1928). Osebergfunnet II : Kongsgaarden, Oslo.

Ingstad, A. S. (2006). Brukstekstilene. In: A. E. Christensen – M. Nockert (eds.). Oseberg-funnet. Bind IV: Tekstilene, Oslo, 185–276.

Jakovleva 2016 = Яковлева, Е. А. (2016). Камерное погребение 3 // Древнерусский некрополь Пскова X – начала XI в.: В 2 т. Т. 2. Камерные погребения древнего Пскова X в. (по материалам археологических раскопок 2003 – 2009 гг. у Старовознесенского монастыря), СПб., 109–165.

Nicolaysen, Nicolay (1882). Langskibet fra Gokstad ved Sandefjord = The Viking-ship discovered at Gokstad in Norway, Kristiania.

Paulsen, Peter (1992). Die Holzfunde aus dem Gräberfeld bei Oberflacht und ihre kulturhistorische Bedeutung, Stuttgart.

Roesdahl, Else – Sindbæk, Søren (2014). Terminology and general plans. Excavation. Documentation. In: Roesdahl, Else et al. Aggersborg. The Viking-Age settlement and fortress, Aarhus, s. 53-80.

Short, William R. (2010). Icelanders in the Viking Age: The People of the Sagas, Jefferson.

Schietzel, Kurt (1981). Stand der siedlungsarchäologischen Forschung in Haithabu – Ergebnisse und Probleme. Berichte über die Ausgrabungen in Haithabu 16, Neumünster.

Schietzel, Kurt (2022). Unearthing Hedeby, Kiel – Hamburg.

Vedeler, Marianne (2014). The textile interior in the Oseberg burial chamber. In: Bergerbrant, Sophie – Fossøy, Sølvi Helene (ed.). A Stitch in Time: Essays in Honour of Lise Bender Jørgensen, Gothenburg: 281-299.

Vidal, Teva (2013). Houses and domestic life in the Viking Age and medieval period: material perspectives from sagas and archaeology, Nottingham: University of Nottingham.

Østergård, Else (1991). Textifragmenterne fra Mammengraven. In. Iversen, Mette et al. (1991). Mammen. Grav, kunst og samfund i vikingetid, Århus 1991: 123-138.

2 responses

I am very interested in this article, partly because I have been writing a history of St Kilda, off the west coast of the Western Isles of Scotland; it is to be published in the autumn. I am developing the idea that the people of St Kilda started to pay their ‘taxes’ in seabird feathers, and perhaps develop a commercial trade in this commodity, during the time of the Norse hegemony in northern and western Scotland. I don’t know if you have any comments on this.

One query, if I may. Do you know of any references to ram-fighting in the literature on the Norse? I believe that the Norsemen imported ‘their own’ variety of sheep to St Kilda, a variety of sheep with four or more very impressive horns (these sheep are known as ‘Hebrideans’ nowadays, and you can see pictures of them on the internet). ASny help or thoughts would be very much appreciated.

Dear Mr. Fleming.

Thank you for your interesting comment. I am not aware of any mention of ram-fighting (unlike the horse fights).

Have a nice day

Tomáš