On March 30 1943, Universitetets Oldsaksamling in Oslo gained the information that a farmer named Lars Gjermundbo found and dug into a huge mound on his land near the farm of Gjermundbu, Buskerud county, southern Norway. The place was examined by archaeologists (Marstrander and Blindheim) the next month and the result was really fascinating.

The mound was 25 meters long, 8 meters broad in the widest place and 1.8 meters high in the middle part. The most of the mound was formed by stony soil; however, the interior of the middle part was paved with large stones. Some stones were found even on the surface of the mound. In the middle part, about one meter below the surface and under the stone layer, the first grave was discovered, so called Grav I. 8 meters from Grav I, in the western part of the mound, the second grave was found, Grav II. Both graves represent cremation burials from the 2nd half of the 10th century and are catalogized under the mark C27317. Both graves were documented by Sigurd Grieg in Gjermundbufunnet : en høvdingegrav fra 900-årene fra Ringerike in 1947.

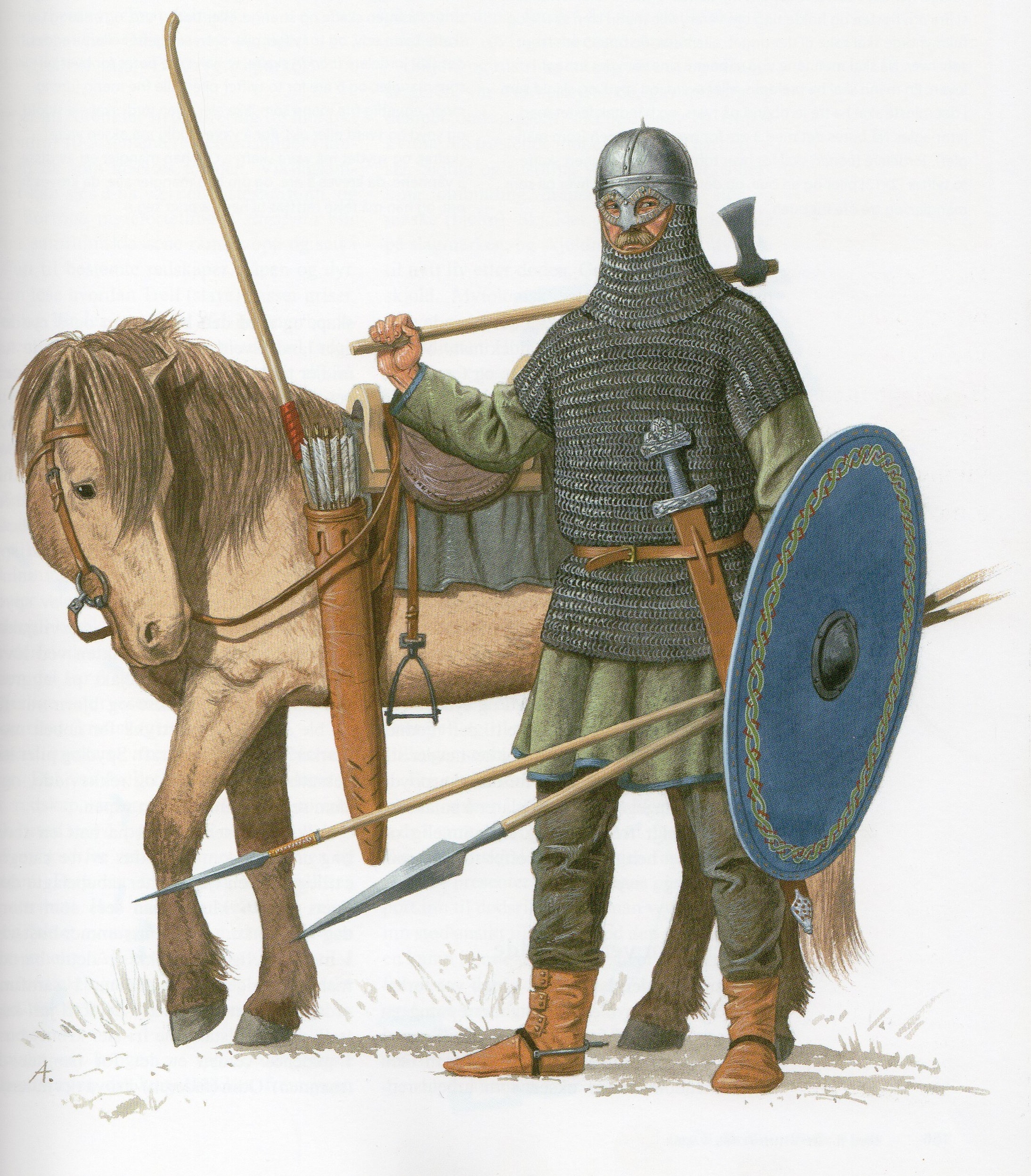

Grav I consists of dozens of objects connected to personal ownership and various activities, including fighting, archery, horse riding, playing games and cooking. Among others, the most interesting are unique objects, like the chain-mail and the helmet, which became very famous and are mentioned or depicted in every relevant publication.

The helmet is often described as being complete and being the only known Viking Age helmet we know. Unfortunately, it is not true, for at least two reasons. Firstly, the helmet is not by any means complete – it shows heavy damage and consists of only 17 fragments in the current state, which means one-fourth or one-third of the helmet. To be honest, fragments of the helmet are glued onto a plaster matrix (some of them in the wrong position) that has the rough form of the original helmet. Careless members of academia present this version as a reconstruction in the museum and in books, and this trend is then copied by reenactors and the general public. I have to agree with Elisabeth Munksgaard (Munksgaard 1984: 87), who wrote: “The Gjermundbu helmet is neither well preserved nor restored.“

The current state of the helmet. Picture taken by Vegard Vike.

Secondly, there are at least 5 other published fragments of helmets spread across Scandinavia and areas with strong Scandinavian influence (see the article Scandinavian helmets of the 10th century). I am aware of several unpublished depictions and finds, whose reliability can not be proven. Especially, helmet fragments found in Tjele, Denmark, are very close to Gjermundbu helmet, since they consist of a mask and eight narrow metal bands 1 cm wide (see the article The helmet from Tjele). Based on the Gjermundbu helmet, Tjele helmet fragments and Kyiv mask (the shape of the original form of Lokrume fragment is unknown), we can clearly say that spectacle helmet type with decorated mask evolved from Vendel Period helmets and was the most dominant type of Scandinavian helmet until 1000 AD, when conical helmets with nose-guards became popular.

To be fair, the helmet from Gjermundbu is the only spectacle type helmet of the Viking Age, whose construction is completely known. Let’s have a look at it!

My mate Tomáš Cajthaml made a very nice scheme of the helmet, according to my instructions. The scheme is based on Grieg´s illustration, photos saved in the Unimus catalogue and observations made by researcher Vegard Vike.

The dome of the helmet is formed by four triangular-shaped plates (dark blue). Under the gap between each two plates, there is a narrow flat band, which is riveted to a somewhat curved band located above the gap between each two plates (yellow). In the nape-forehead direction, the flat band is formed by a single piece, that is extended in the middle (on the top of the helmet) and forms the base for the spike (light blue; the method of attaching the spike is not known to me). There are two flat bands in the lateral direction (green). Triangular-shaped plates are riveted to each corner of the extended part of the nape-forehead band. A broad band, with visible profiled line, is riveted to the rim of the dome (red; it is not known how the ends of this piece of metal connected to each other). Five rings were connected to the very rim of the broad band, probably remnants of the aventail. In the front, the decorated mask is riveted onto the broad band.

© 2016 Kulturhistorisk museum, UiO

Since all known dimensions are shown in the scheme, let me add some supplementary facts. Firstly, four somewhat curved bands are shown a bit differently in the scheme – they are more curved in the middle part and tapering near ends. Secondly, the spike is a very important feature and rather a matter of aesthetic than practical usage. Regarding the aventail, rings were found around the brim, having the spacing of 2,4-2,7 cm. On contrary to chain-mail, rings from the helmet are very thick and probably butted, since no trace of rivets were found. It can not be said whether they represent the aventail, and if so, what it looked like and whether the aventail was hanging on rings or on a wire that was drawn through the rings (see my article about hanging devices of early medieval aventails). The maximum number of rings used around the brim is 17. Talking about the mask, X-ray showed at least 40 lines, which form eyelashes, similarly to Lokrume helmet mask (see the article The helmet from Lokrume). The lines are too shallow for inlayed wires. Instead, lead-copper-tin alloy was applied and melted during the cremation. The mask shows a two-part construction, overlaped and forge-welded at each temple and in the nose area (according to the X-ray picture taken by Vegard Vike). There is a significant difference between the thickness of plates and bands and the mask; even the mask shows uneven thickness. Initially, the surface of the helmet could be polished, according to Vegard Vike.

I believe these notes will help to the new generation of more accurate reenactors. Not counting rings, the helmet could be formed from 14 pieces and at least 33 rivets. Such a construction is a bit surprising and seems not so solid. In my opinion, this fact will lead to the discussion of reenactors whether the helmet represents a war helmet or rather a ceremonial / symbolical helmet. I personally think there is no need to see those two functions as separated.

I am very indebted to my friends Vegard Vike, who answered all my annoying question, young artist and reenactor Tomáš Cajthaml and Samuel Collin-Latour. I hope you liked reading this article. If you have any question or remark, please contact me or leave a comment below. If you want to learn more and support my work, please, fund my project on Patreon or Paypal.

Bibliography

GRIEG, Sigurd (1947). Gjermundbufunnet : en høvdingegrav fra 900-årene fra Ringerike, Oslo.

HJARDAR, Kim – VIKE, Vegard (2011). Vikinger i krig, Oslo.

MUNKSGAARD, Elisabeth (1984). A Viking Age smith, his tools and his stock-in-trade. In: Offa 41, Neumünster, 85–89.

17 responses

Hello! , I wanted to ask about some interpretations made by some blacksmiths on this helmet in black color, is not it? Can it be taken up? Thank you very much for this blog, I am reading about the topics that are posted !!!

Dear Paul.

As I wrote in the article “Initially, the surface of the helmet could be polished, according to Vegard Vike.” I imagine early medieval helmets as shiny and bright objects and some written sources and archaeological finds prove that (some of them were coated with bronze of gilded. for example). As far as I know, there is no proof of blackened helmets. It would be better if you sent me the picture.

Have a nice day!

Tomáš

Many thanks for replying tomás :), I was a little confused to see an interpretation made by thorkil ( http://www.thorkilshop.com/communities/9/004/012/133/759/images/4613671473.jpg ), in Which was guided by the image made by you, but now I know that it should only be bright and polished! 😀

Have a nice day!! 🙂

Hello. I was wondering if you would be able to tell me something I’ve never fully understood?

Exactly how much of the helmet is actually found?

In the first picture from “2016 Kulturhistorisk museum, UiO”, the part left of the center band seems thick and has a rusty metal texture. The right side seems much smoother.

Is the right part just part of the museum display, or part of the actual helmet? Because it kind of looks like an internal plate or something. Is this the “plaster matrix” you mention?

Hello René.

Only a 1/5 or 1/4 survived. Basically, the smooth part is what I call plaster matrix. It is a modern model which serves as the support for the fragments.

Best regards,

Thomas

By the way which do you think is more likely, should the four plates be over, or under the browband?

Hello!

Thank you for your message. If our illustration is correct, the plates are located under the browband. I know that a lot of reenactors use the other method. Vegard Vike is now writing an article about the helmet, and the results will probably force me to rewrite this work.

Thank you for your reply. The odd construction of the helmet has puzzled me for a while. It certainly isn’t as sturdy as the normal spangenhelm construction. Is it easier to construct? It certainly seems to be intentional since the fragments from Tjele indicate a similiar construction. What might be the reason for this construction?

Hi, do you think the helmet had cheek flaps, to compliment a small aventail?

Dear Russ,

we do not have any evidence for cheek flaps after 800 AD in Europe.

Hallo!

Please tell me how the burial with the helmet is now dated. On the Internet, I came across the following dates: second half of the 10th century; about 970; the beginning of the 11th century.

Thanks)

Hello!

Thank you very much for your message. Because of the Petersen type S sword, the scabbard chape and other components of the grave, it can be easily dated to the 2nd half of 10th century, 975 being the closest dating.

Have a wonderful day!

Thomas

sagy.vikingove.cz

dear thomas,

thanks for your work! what do we actual know about the inlay material? I read Vegard was investigating on this but I don’t know of any results, do you?

Hey Tomas, im interested in reading the article/book by Elisabeth Munksgaard that you reference. Do you know where to find it? I’ve tried looking for it, im curious how you got to read it.

Hello Baltazar,

thank you very much for your message. I am sending you link via email.

Have a nice day

Tomáš

Hello, very nice article, do you know why do we call it Gjermundbu, while the farmer’s family name is Gjermundbu, and why it is call after them rather than the nearest town like the Tjele helmet ? Thank you for your amazing work

Hello Gab, thank you. It is because of the farm that was named after the farmer.