For about 15 years now, I regularly encounter attempts to reconstruct Early Medieval helmets and I myself am one of the owners and frequent users of these items. I observe that during this period there was a significant shift in our knowledge of Early Medieval helmets, which was caused both by the development of the digital medium and the advent of a new generation of researchers and the emergence of new platforms devoted to medieval militaria. I have personally contributed to the process of documentation of helmets by a total of eleven articles on this platform, many of which have been cited in the academic press. Despite all this, the helmets of the Early Middle Ages remain very poorly researched, which causes frequent mistakes in their interpretation and reconstruction.

Besides the incorrect construction, too wide mask and long nose guards, one of the most significant shortcomings in terms of the visual aspect of helmets is the use of an inappropriate method of mail suspension. While the previously mentioned shortcomings have been gradually eliminated over time, methods of attaching the chain mail neck protection are a constant problem. The absolute standard in both the reenactor and academic spheres is the idea that helmets had drilled holes all around, into which the rings were directly inserted. For this reason, I decided to map the methods of fixing the mail in 5th-12th century Europe, taking into account the Middle East, Siberia and Egypt in the same period. With a total number of about a hundred helmets involved, the work is one of the most significant syntheses in the field. This article can be used both by reenactors, who can design their helmets more accurately, and in the academic community. In many cases, I am forced to use old drawings, so it’s possible that I inadvertently made mistakes that I’m happy to fix. Errors are also possible due to the fact that the helmets exhibited in museums are partially reconstructed and do not correspond to the original appearance.

Before beginning the synthesis itself, it must be said that a large part of the Early Medieval helmets do not show any of the presented methods. It is very possible that these helmets were not equipped with neck protection, as some iconography suggests (eg Graham-Campbell 1980: Cat. No. 482), or neck protection was not a direct part of the helmet, for example in the case of the mail coifs, which were integral parts of the body armours. If the helmet had a hanger, it could take several forms:

1. from ear to ear

The mail extending roughly from ear to ear can be found on some helmets that have cheek guards, such as the Coppergate helmet. In Frankish and Byzantine iconography, a number of helmets with neck protection can be found that correspond to this length of mail, eg the Stuttgart Psalter (WLB Cod. Bibl. Fol. 23), 5v, 8r, 21v; Book of Maccabees (UBL Cod. Perizoni F.17), 15v, 16r.

2. from eye to eye without a covered throat

The mail that reaches the eyes (or the mask) and is not connected in front of the face to protect the throat is assumed for the St. Wenceslas helmet. In iconography it can be found in eg in the Pictures from the Life of St. Albino of Angers (NAL 1390), 7. The same method seems to be used in Silos Apocalypse (BL Additional 11695), 194r.

3. from eye to eye with covered throat

The mail that reaches the eyes (or the mask) and is connected in front of the face to protect the throat was used at the helmet from the grave Valsgärde 8 and is assumed for one-piece conical helmets with a hook on the nose guard. In iconography, it is difficult to distinguish this method from coifs, which are integral parts of armours. There are both variants with nose guards, eg Office Lectionary (Orléans BM MS.342), and variants without a nose guard, eg the Golden Codex from Ecternach (GNM Hs. 156142); Bible (BNF Latin 8 [1]), 91r.

Different size of mail neck protection – from ear to ear, from eye to eye without covered neck, from eye to eye with covered neck. Archive of Dmitri Chramcov, Roman Král and Makar Babenko.

Different size of mail neck protection – from ear to ear, from eye to eye without covered neck, from eye to eye with covered neck. Archive of Dmitri Chramcov, Roman Král and Makar Babenko.

The rings of the mail can be oriented in two directions, namely:

1. horizontally

The mail extends to the sides. This method can be found on helmets from Valsgärde 8, Coppergate, Kazazovo and “Russian Chambers”. The method seems to be used especially when the mail is fixed continuously, eg by wire or sewing to the substrate.

2. vertically

The mail extends downwards. This method can be found on helmets from Klimovskij Rayon (Radjuš 2019: рис. 5A) and Egypt (Brooklyn museum 2020). The method seems to be used in particular when the mail is fixed at larger intervals, namely for subtypes 2.1 and 3.8.

Mail orientation:

Mail orientation:

horizontal (left, manufacturer royaloakarmoury.com), vertical (right, Radjuš 2019: рис. 5A).

Interestingly, at least one helmet – namely the find from mound No. 86 (18) of Gnezdovo – was equipped with a mail protectors, which was made of rings with a smaller diameter than those used in the armour found in the same grave. While the armour rings have an inner diameter of 6–8 mm with a wire thickness of 1.5 mm, the helmet mail is made of rings with an inner diameter of 4 mm with a wire thickness of 1 mm (Vlasatý 2018a). The helmet mail of one of the Stromovka helmets is made of a very similar material, rings with an inner diameter of 4.5-5 mm and a wire thickness of 1 mm (Vlasatý 2018a). The question arises as to whether this small diameter was intentionally used to be able to withstand arrows or other deeply penetrating weapons. The two sovereign deaths of 1066 AD clearly show us that the head and neck area was an attractive target for archers, so the assumption would not be illogical.

However, we do not see this phenomenon in other well-researched helmets – for example, the rings of the Bojná helmet have an inner diameter of 7 mm and 1 mm thick wire (Vlasatý 2018a) and the mail of the Coppergate helmet is made of rings with an inner diameter of 5.8-6 mm and wire thickness of 0.9-1.2 mm (Tweddle 1992: 1003). I believe that the rings from Birka contribute to the debate, from which it is possible to read how a huge range of diameters was used within one locality (inner diameter: 4-12.6 mm, wire thickness 1-4 mm; Ehlton 2003). From the available information, it appears that a thinner wire with a diameter of about 1 mm was chosen for the production of the helmet mail, which may be related to the weight carried on the head. The inner diameter of the rings is then related to the solvency of the owner. At this point we can mention a contrast from the world of body armour: mail of St. Wenceslas armour, which has probably the finest rings of the Early Middle Ages, have an inner diameter of 3.3-4.1 mm with a wire thickness of 0.9-1.1 mm (Bravermanová et al. 2019: 248), while the rings used on Gjermundbu armour is significantly denser and more massive at an inner diameter of 4.7-5.2 mm and a wire thickness of 1.2-1.9 mm (Vike 2000).

As mentioned elsewhere on this site (Vlasatý 2018a), some of the helmet mails were adorned with copper or gold alloy rings.

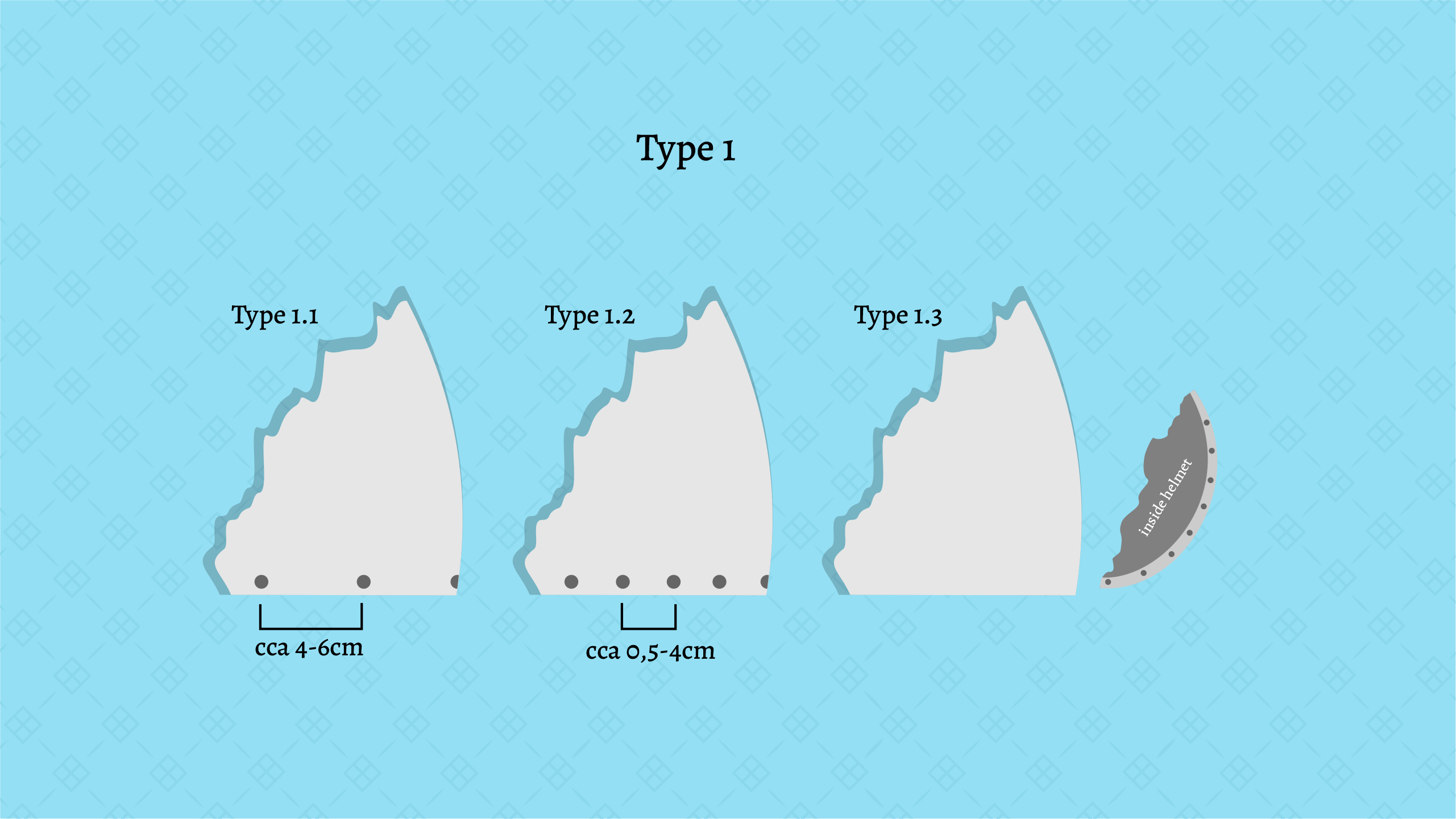

Methods of mail suspension of type 1. Better resolution here. Produced by Tomáš Cajthaml.

Methods of mail suspension of type 1. Better resolution here. Produced by Tomáš Cajthaml.

Type 1

This type describes the edge of a helmet which is not reinforced by an additional band and into which holes are formed at regular intervals which are not filled with metallic material.

Subtype 1.1

Helmets belonging to this subtype are characterized by holes evenly distributed over a large part of the entire circumference of the helmet at intervals of approximately 4-6 cm. In some cases, the holes are located in the space above the eyes, which suggests that these holes were designed to attach the organic liner of the helmet, to which mail neck protector could be attached, the existence of which in the case of one-piece conical helmets is evidenced by a hook protruding from the tip, serving to secure the mail in front of the throat (Sankiewicz 2018: 126). The mail protector itself is not found in connection with helmets belonging to this subtype.

Specimens of this subtype are found mainly in three large groups. The most dominant group are conical one-piece helmets – this includes both helmets from Hradsko (Bernart 2010: 18-22), a helmet from Olomouc – proboštství (Bernart 2010: 44-48), most probably also a helmet from Olomouc – les (Bernart 2010: 49 ), helmet from Lake Lednice and Orchowski (Sankiewicz 2018). There are also other conical helmets corresponding to this subtype in the literature and European collections, the authenticity of which cannot be verified and which in some cases are likely to be counterfeit (eg D’Amato 2015: Fig. 31.1, the helmet exhibited at the Museo delle Armi Luigi Marzoli in Brescia, Italy, the helmet sold at auction Hermann Historica). The second group represent East European helmets of a spheroconical shape with an eight-part dome and a nose guard, including a helmet from Stolbišče (Oskol) and the Krasnodar region (Kainov 2017). The third group consists of Baltic helmets of the Dollkeim type, belonging to the 12th-13th century, among which we can name helmets from the localities Kleinheide and Kovrovo (Skvorcov 2014). Aside from these groups are helmets from Lukašovka, Moldova (D’Amato 2015: Pl. 12) and the Romanian locality of Vatra Moldoviței (D’Amato 2015: Pl. 21-22), dated to 12th-13th century. This subtype was further used in the Middle Ages (eg Michalak – Glinianowicz 2013).

Suggested reconstruction of the subtype 1.1, owner Jan Zbránek.

Suggested reconstruction of the subtype 1.1, owner Jan Zbránek.

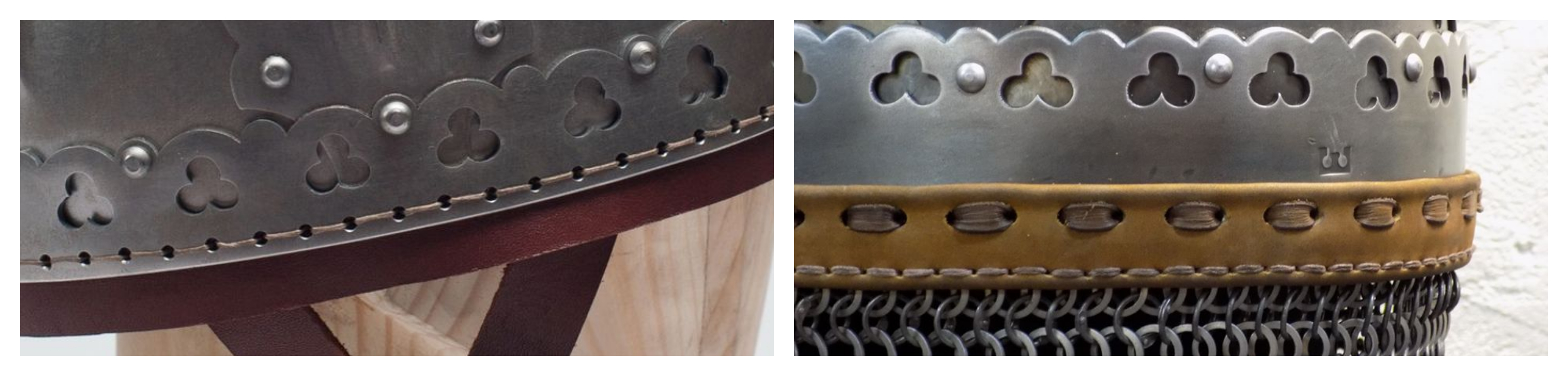

Subtype 1.2

Helmets belonging to this subtype are characterized by holes evenly distributed over a large part of the entire circumference of the helmet at intervals of approximately 0.5-4 cm. Despite the popular idea that numerous holes were used to insert the rings, the exact opposite is confirmed – the holes were used to fasten organic padding, edging the helmet with organic material or to fasten an organic strip to hang the mail. This is evidenced by:

1. absence of rings in the holes, with the exception of subtype 2.1, which was filled with butted rings with an interval no smaller than 2 cm.

2. the existence of holes even in the space above the eyes. A specific case leading to the same reading of holes is the helmet mask from Nikolskoye (13th century), which is densely perforated, while the remaining edge of the helmet does not indicate the use of a mail protector (Kirpičnikov 1971: Table XVI).

3. the presence of holes even in the case of the use of cheek guards (James 1986: Fig. 1, 5-6).

4. dense perforatation of components, such as cheek guards, indicating the original edging (Brooklyn museum 2020; D’Amato 2015: Pl. 3-4).

5. rivets filling the holes of some later analogies (Kulešov 2017: Рис. 7).

6. later analogies, such as bascinets, which show that the holes at the edges were used to install the liner, while the eyelets of subtype 2.2 were used to fasten the mail (see also the specimen from Ozana in D’Amato 2015: Pl. 2).

Equally interesting is the lamellar helmet from Niederstotzingen, whose numerous holes were used to lace up the components together and hem them (Paulsen 1967: 133-9). In connection with this subtype, mail neck protector was find together with finds from the localities Pakalniškiai and Peški.

Numerous holes on the edges of helmets are a widespread phenomenon that can be observed in a number of late Roman helmets and helmets of the migration period (type Intercisa, spangenhelms helmets of the Egyptian group, type Baldenheim, Langobard helmets, Sasanian helmets, see Hejdová 1964: 43-68). They are also found on conical helmets of the Baltic type, which are dated to 11th-13th century – especially helmets from the localities Pakalniškiai and Rusių Ragas (Volkaitė-Kulikauskienė 1965). The holes are also located on multi-piece spheroconical and one-piece conical Eastern European helmets dated to 11th-13th century, especially helmets from Novorossiysk, Astrakhan, Ukraine (Arendt 1936: 32; Kirpičnikov 1971: Table XIII) and Babiči (Kirpičnikov 1971: Table XI). This subtype can also be assigned a helmet from the Belarusian Slonim, dated to 12th-13th century (Plavinski 2013: 80-3). Tibetan-type helmets and helmets from the Golden Horde period, which are represented in Europe by finds from Verden (Kubik 2016; Kubik 2017; Wilbrand 1914) and the Peški locality (Kirpičnikov 1971: Табл. XV), also have densely perforated edges. In the literature and European collections, there are also conical one-piece helmets corresponding to this subtype, the authenticity of which cannot be verified and which in some cases are probably counterfeits (eg D’Amato 2015: Fig. 31.2). This subtype was further used in the Middle Ages (eg Michalak – Glinianowicz 2013: Fig. 2).

Suggested reconstruction of the subtype 1.2, maker Fay armoury.

Suggested reconstruction of the subtype 1.2, maker Fay armoury.

Subtype 1.3

Helmets belonging to this subtype are characterized by holes evenly distributed over a large part of the entire circumference of the helmet at intervals of approximately 4-6 cm, which are located on a vertical brim. This atypical location adds to the idea that the holes are not related to the attachment of the helmet liner, and could hold the mail neck protector. We know this subtype from only one find that was recently published – helmet from Yarm, England (Caple 2020).

Suggested reconstruction of the subtype 1.3, maker Dmitry Chramcov.

Suggested reconstruction of the subtype 1.3, maker Dmitry Chramcov.

Methods of mail suspension of type 2. Better resolution here. Produced by Tomáš Cajthaml.

Methods of mail suspension of type 2. Better resolution here. Produced by Tomáš Cajthaml.

Type 2

This type describes the edge of a helmet which is not reinforced by an additional band and into which holes are formed at regular intervals which are filled with a metallic material.

Subtype 2.1

Helmets belonging to this subtype are characterized by holes evenly distributed over a large part of the entire circumference of the helmet at intervals of approximately 2-3 cm, which are filled with butted rings of thick wire. The mail protector could be connected in such a way that it was threaded on a wire which was passed through the rings along the entire circumference. An alternative suspension option is that the rings were directly connected to the mail. Importantly, however, these connection rings were not riveted.

We know this subtype from only two find, the helmet from the Gjermundbu, Norway (Grieg 1947; Vlasatý 2016), which retains 5 rings along the edge with a spacing of 2.4-2.7 cm, and a Baldenheim type helmet found in Klimovskij Rayon, Russia (Radjuš 2019: рис. 5A).

Suggested reconstruction of the subtype 2.1, maker Dmitry Chramcov.

Suggested reconstruction of the subtype 2.1, maker Dmitry Chramcov.

Subtype 2.2

Helmets belonging to this subtype are characterized by holes evenly distributed over a large part of the entire circumference of the helmet at intervals of approximately 4-6 cm, which are filled with omega-shaped eyelets – the legs of the eyelets are inside the helmet, while the loops protrude through the holes outside the helmet. A wire was passed through these eyelets, on which hung the mail protector. A good specimen with a preserved mail suspension is the helmet from Kazazovo.

Helmets of this subtype include spheroconical helmets from Giecz (Poklewska-Koziełł – Sikora 2018), Olszówka (Rychter – Strzyż 2016: Fig. 9), Pécs (Nagy 2000), Kazazovo (Slanov 2007: Табл. LV) and Gulbišče (Samokvasov 1916: 36-8; Kirpičnikov 2009: рис. 11.2). The subtype also includes a helmet from Ozana, Bulgaria, which older literature ranks in the 9th-10th century (Hejdová 1964: 83; D’Amato 2015: Pl. 2), but the current literature, due to its similarity to bascinets, describes it as a product of the 13th-14th century (Rabovyanov – Dimitrov 2017: 39-40). It is thus probable that this method was also applied in the High Middle Ages. This subtype is related to subtype 3.3 and they both should be understood as variants of the same group in the subsequent studies.

Suggested reconstruction of the subtype 2.2, makers Мастерская “МОЛОТ”, True History Shop.

Suggested reconstruction of the subtype 2.2, makers Мастерская “МОЛОТ”, True History Shop.

Subtype 2.3

Helmets belonging to this subtype are characteristic by holes evenly distributed over a large part of the entire circumference of the helmet at intervals of approximately 0.5-6 cm, to which eyelets of profile P made of bent sheet metal are attached from the visible side by rivets. A wire was passed through these eyelets, on which hung the mail protector. Helmets from the Durso and Moldavanskoye are good specimens with a preserved mail suspension.

This subtype is located on three helmets from the Krasnodar region, specifically graveyards Karla Marksa, Durso and Moldavanskoye (Kainov – Menšikov – Rukavišnikova 2020: 208, рис. 5-6). The same solution can be seen on the edges of late Roman helmets from the localities of Turajevo and Caricyno (Kubik – Radjuš 2019). This subtype is related to subtype 3.5 and they both could be understood as variants of the same group in the subsequent studies.

The helmet from graveyard Karla Marksa. Kainov – Menšikov – Rukavišnikova 2020: 208, рис. 5.4, рис. 6.

The helmet from graveyard Karla Marksa. Kainov – Menšikov – Rukavišnikova 2020: 208, рис. 5.4, рис. 6.

Subtype 2.4

Helmets belonging to this subtype are characterized by holes evenly spaced approximately 4-6 cm apart, to which bent sheet metal eyelets are attached on both sides by rivets. A wire was passed through these eyelets, on which hung a mail protector. This subtype occurs only on the smaller helmet from Braničevo (D’Amato – Spasić-Đurić 2018) and is related to subtype 3.6; they both should be understood as variants of the same group in the subsequent studied.

The smaller helmet from Braničevo. D’Amato – Spasić-Đurić 2018: Fig. 17.

The smaller helmet from Braničevo. D’Amato – Spasić-Đurić 2018: Fig. 17.

Subtype 2.5

Helmets belonging to this subtype are characterized by evenly spaced holes to which bands with two bent eyelets are attached by rivets. A wire was passed through these eyelets, on which hung the mail protector. We know this subtype only from the helmet from the grave Valsgärde 6. In case of the helmet, the bands are spaced about 2-3 cm apart and the mail protector was found together with the helmet (Arwidsson 1942: 28–9, Abb. 20, 27-8). This subtype is related to subtype 3.7 and they both should be understood as variants of the same group in the subsequent studies.

The helmet from the grave Valsgärde 6. Arwidsson 1942: Abb. 20, 27-8.

The helmet from the grave Valsgärde 6. Arwidsson 1942: Abb. 20, 27-8.

Methods of mail suspension of type 3. Better resolution here. Produced by Tomáš Cajthaml.

Methods of mail suspension of type 3. Better resolution here. Produced by Tomáš Cajthaml.

Type 3

This type describes the edge of the helmet, which is reinforced by an additional band that participates in the system of padding the helmet or the system of mail suspension.

Subtype 3.1

Helmets belonging to this subtype are characterized by an additional band equipped with holes evenly distributed over a large part of the helmet at intervals of approximately 0.5-5 cm. Despite the popular notion that numerous holes were used to insert the rings, the exact opposite is confirmed – as in the case of subtypes 1.1-1.2, the holes were used to fasten the organic liner or to edge the helmet with organic material. In the case of a helmet from Niederrealta, an organic liner was found inside, which was attached through the mentioned holes. In connection with helmets belonging to this subtype, the mail protector was found together with the helmet from Gnezdovo.

Helmets with this subtype include two helmets from Chamoson (Geßler 1929; D’Amato 2015: Pl. 8) and Niederrealta (Schneider 1967). Helmets of this subtype also include spheroconical helmets from Gnezdovo (Kainov 2019: 191-6, рис. 72; Sizov 1902: 65-7, рис. 16) and Gniezno (Hensel 1987: 191). The helmet from Nemia can also be assigned to this subtype, as it is equipped with a double-sided band (Kirpičnikov 1971: Table IX). From non-European finds of the Early Middle Ages, a Khitan helmet from the Zabaykalsky Regional Museum can be assigned to this subtype (Bobrov 2013). An affiliation of some spheroconic helmets, which were originally fitted with a perforated decorative band – such as a helmet stored at the Royal Armories Museum in Leeds, UK (Beard 1922), a helmet from Mokroe (Bocheński 1930) or one of the segments found in Ukraine (Papakin – Bezkorovajnaja – Prokopenko 2017: рис. 1-4) – to this subtype is problematic. This subtype is an extension of subtypes 1.1-1.2 and all of them should be understood as variants of the same group in the subsequent studies.

Suggested reconstruction of the subtype 3.1, makers Kvetun, Fay armoury.

Suggested reconstruction of the subtype 3.1, makers Kvetun, Fay armoury.

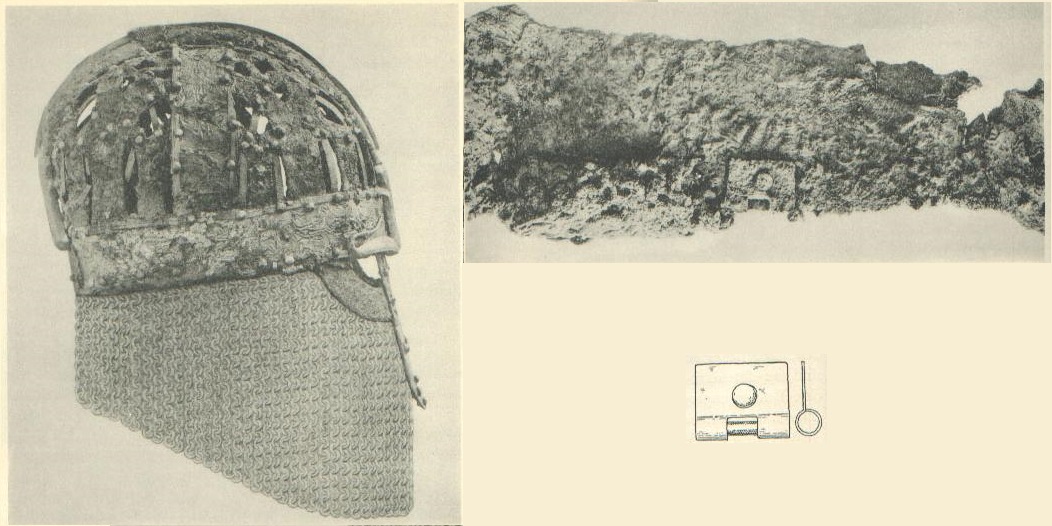

Subtype 3.2

Helmets belonging to this subtype are characterized by an additional band riveted to the view side, the band being provided on the underside with teeth which are bent inwards so as to form circular eyelets. The resulting band has a P-profile. A wire is passed through the eyelets, on which a mail protector is hung, the rings of which are inserted into the notches between the teeth.

We know this subtype of suspension from at least one helmet from the Black Mound (Samokvasov 1916: 7-8, Kirpičnikov 2009: 63, рис. 46) and from the recently discovered helmet, which is published by A. N. Kirpičnikov and which is stored in the gallery “Russian Chambers” (Kirpičnikov 2009: 6-8). The bands of both of these helmets are iron and silver-plated. In both cases, the helmets are accompanied by the mail protectors. This method persisted in Eastern Europe until the High Middle Ages, as indicated by a series of helmets from the 13th century, which are equipped with iron belts with relatively wide teeth (Kulešov 2017).

Suggested reconstruction of the subtype 3.2, maker True History Shop.

Suggested reconstruction of the subtype 3.2, maker True History Shop.

Subtype 3.3

Helmets belonging to this subtype are characterized by an additional band riveted to the view side, with a large part of this band drilled approximately 4-6 cm apart. The holes are filled with omega-shaped eyelets – the legs of the eyelets are inside the helmet, while the loops protrude through the holes outside the helmet. A wire was passed through these eyelets, on which hung a mail protector.

Good examples of this subtype are helmets from Gorzuchy (Rychter – Strzyż 2016: Fig. 10.2), Lviv region (Vlasatý 2020), Manvelovka (Čurilova 1986) and Novgorod (Kainov – Kamenskij 2013). The Poltava Regional Museum also exhibits a helmet belonging to the Black Mound type, which suffered significant damage during World War II and is now partially reconstructed with a similar subtype (Papakin – Bezkorovajnaja – Prokopenko 2017). This subtype is an extension of the subtype 2.2 and they both should be understood as variants of the same group in the subsequent studies.

Suggested reconstruction of the subtype 3.3, owner Jan Seman.

Suggested reconstruction of the subtype 3.3, owner Jan Seman.

Subtype 3.4

Helmets belonging to this subtype are characterized by an additional band, which is bent in half and riveted to the visible and inner side of the helmet. The resulting band has a U-profile. There are notches in the bend of the strip. A wire is passed through the band, on which a mail protector is hung, the rings of which are inserted in the notches. This is a laborious method ensuring quality attachment, which is evident from the frequent preservation of the mail protectors in case of this subtype.

This subtype is used in several groups of European helmets. The first group are the helmets of the Vendel Period, which include the helmets from Valsgärde 7 (Arwidsson 1977: 23, Abb. 24), Valsgärde 8 (Arwidsson 1954: 24, Abb. 10), Vendel XII (Stolpe 1912: Fig. 8, Pl. XXXVI; Lindqvist 1950: Figs. 3, 4, 9) and probably also Rickeby (Sjösvärd – Vretemark – Gustavson 1983). In all of these helmets, the belts are made of copper alloy. Some Vendel Period helmets have a band covered on the outside with a more profiled and less riveted band, which at the same time holds the embossed decorations in place. The band of Coppergate helmet, which is also made of a copper alloy, stands close to this group (Tweddle 1992: 960–965, 999–1003, 1052–1053).

The second larger group are helmets of the Stromovka type, which include both helmets from Prague-Stromovka (Hejdová 1964: 49-54), the helmet from Gnezdovo (Sizov 1902: 97–100; Kainov 2019: 188-191, рис. 72; Kirpičnikov 1971: 21, Table X.1) and the helmet from Bojná (Vlasatý 2018a). All four helmets of this type have bands made of iron. The helmet from the Trnčina, Bosnia (Shchedrina – Kainov in press), which is equipped with an iron band, stands close to this group.

The St. Wenceslas helmet falls into a similar category as the helmet from Trnčina; the edge of the St. Wenceslas helmet was originally equipped with a silver band of the same subtype, of which only fragments are now visible (Bravermanová et al. 2019: Figs. 65, 67). The fragment from Birka, which is made of a gold-plated copper alloy (Vlasatý 2015a), most probably belongs to the same subtype. The helmet stored in the Dmitry Javornicky National Historical Museum in Dnepropetrovsk (D’Amato 2015: Fig. 50.3; Shchedrina – Kainov in press) is equipped with the same subtype made of iron. According to information that cannot be verified due to the poor condition of the helmets, subtype 3.4 remained in Eastern Europe until the High Middle Ages (Shchedrina – Kainov in press).

Reconstruction of the mail suspension of the Coppergate helmet. Taken from Tweddle 1992: 1000, Fig. 462.

Reconstruction of the mail suspension of the Coppergate helmet. Taken from Tweddle 1992: 1000, Fig. 462.

Suggested reconstruction of the subtype 3.4, owner Michal Bazovský.

Suggested reconstruction of the subtype 3.4, owner Michal Bazovský.

Subtype 3.5

Helmets belonging to this subtype are characterized by an additional band riveted to the inner side, with a huge number of P-profile eyelets being riveted on the band at small intervals. A wire is passed through these eyelets, on which hung the mail protector, or rings were hung directly on the eyelets. An alternative is that the rivets held an organic belt on which the the mail hung.

Helmets of this type are conspicuous by the band riveted to the inner side of the edge, and therefore it is relatively easy to distinguish them in the archaeological material. The most famous example is the helmet from Lagerevo, which has a series of non-ferrous metal rivets and fragments of eyelets preserved on the band (Mažitov 1981: рис. 42). However, the best example of this type is the helmet from Starica (Ožeredov 1987: 115-8, Рис. 2; Solovjev 1987: Табл. XIV.1). Another analogy, but without preserved eyelets, is the helmet from the Relka (Solovjev 1987: Табл. XIV.2). The Perm Regional Museum houses a well-preserved helmet of the same type, the rivets of which hold organic fragments, indicating the absence of eyelets (Wierzbowski 2016: Rys. 4.4). A very good analogy of the helmet from Starica, but with a band probably riveted to the outside of the edge, is the newly discovered helmets from Petra, Georgia, dated to the 6th century (personal discussion with Adam Kubik). This subtype is most likely an extension of subtype 2.3 and they both could be understood as variants of the same group in the subsequent studies.

The helmet from Starica. Ožeredov 1987: Рис. 2.

The helmet from Starica. Ožeredov 1987: Рис. 2.

Subtype 3.6

Helmets belonging to this subtype are characterized by holes evenly spaced approximately 4-6 cm apart, to which metal eyelets made of bent sheet are attached by rivets on both sides. A wire was passed through these eyelets, on which hung a mail protector. This subtype occurs in two helmets – on the cheek guards of the Coppergate helmet (Tweddle 1992: 999, Fig. 431) and on the larger helmet from Braničevo (D’Amato – Spasić-Đurić 2018). This subtype is an extension of subtype 2.4 and they both should be understood as variants of the same group in the subsequent studies.

Detail of attaching the mail to the cheek guards of the Coppergate helmet. Tweddle 1992: 999, Fig. 431.

Detail of attaching the mail to the cheek guards of the Coppergate helmet. Tweddle 1992: 999, Fig. 431.

Suggested reconstruction of the subtype 3.6, maker Lykia Historical Armour.

Suggested reconstruction of the subtype 3.6, maker Lykia Historical Armour.

Subtype 3.7

Helmets belonging to this subtype are characterized by evenly spaced pair of holes to which bands with two bent eyelets are attached from the view side, similarly to subtype 2.5. The difference is that the bands are significantly longer and are covered with a more profiled and less riveted band, which holds the embossed decorations in place at the same time. A wire was passed through these eyelets, on which hung a mail protector.

We know this subtype only from the helmet from the grave Vendel I (Stolpe 1912: Pl. VI.1, 8; Lindqvist 1950: Fig. 5-7), on which fragments of copper alloy band are located on the left cheek and on the neck. This subtype is related to subtype 2.5 and they both should be understood as variants of the same group in the subsequent studies.

Detailed look at the edge of the helmet from Vendel I. Stolpe 1912: Pl. VI.1, 8.

Detailed look at the edge of the helmet from Vendel I. Stolpe 1912: Pl. VI.1, 8.

Subtype 3.8

For completeness, we add the subtype, which is characterized by evenly spaced holes with a spacing of about 10 cm, to which are riveted bands that have counterparts and form hinges. The counterparts were directly riveted to the mail. The upper parts of the hinges were covered with yet another band that go around the helmet.

We know this subtype only from the Egyptian helmet exhibited in the Brooklyn Museum (Brooklyn museum 2020; D’Amato 2015: 82, Fig. 36.3). The use of hinges to attach neck protection can also be recorded in other Egyptian helmets (Dêr-el-Medineh; James 1986: Fig. 5-6). However, hinges are also recorded in European helmets, where they serve not only to fasten the cheek guards (Coppergate, Vendel XIV, Wollaston; Tweddle 1992: 989–997; Meadows 1996–7), but mainly to fix metal straps representing neck protection (Broa, Ultuna, Vendel XIV, Valsgärde 5; Lindqvist 1931; Nerman 1969: Taf. 66; Tweddle 1992: Figs. 537, 539, 543-5).

Detailed look at the edge of the helmet from Egypta. Brooklyn museum 2020.

Detailed look at the edge of the helmet from Egypta. Brooklyn museum 2020.

Helmet selection triangle

In the background of the presented methods, there are three ubiquitous variables, among which the manufacturers and users of helmets had to choose compromises. These ideally look like this:

1. complexity of production (price)

Large groups of visually uniform helmets (Black Mound type, one-piece conical helmets with a nose guard, type Stromovka and others) testify to the production in workshops that produced helmets in a uniform style according to established procedures and using tools and jigs specific to the workshop. In relation to the methods of hanging the mail protector, it is clear that the helmets point to dense perforation at the edge only if the dome is segmental or the holes are located on a separate band. In other words, if the helmet could be manufactured in parts and gradually assembled, the more likely it could be provided with numerous holes, which would be achieved in a complicated manner in the case of one-piece helmets.

It is true that the more demanding the production, the more expensive the product. In particular, subtype 3.4 is really a time-consuming method, which is avoided even by today’s craftsmen with modern tools and is replaced by subtype 3.2.

2. protection, strength and maintenance (performance)

All the presented methods, in combination with dense mail, have the potential to provide excellent protection against cutting weapons and, to some extent, perhaps also sufficient protection against arrows or other deeply penetrating weapons. However, the difference was in the strength and durability of individual subtypes. While subtypes 3.4 and 3.2 cover the wire along its entire length and create a smooth divide between the helmet and the mail, other variants more or less expose the wire and the divide is stepped, which can result in the suspension mechanism being cut off or the mail ripped out. It is also necessary to take into account that mechanisms made of non-ferrous materials are more prone to damage.

There is no doubt that helmets were expensive items and were maintained by the hands of professionals – polishers who polished and repaired them, which is in line with another article on this site, where I emphasized the requirements for surface treatment, rust removal, repairs and patching helmets (Vlasatý 2015b). In the light of presented research, we can confirm this idea. In all cases, the methods of mail suspension are designed so that the wire or organic band can be easily removed and the mail suspension can be cleaned or repaired separately, thus leading to easier maintenance.

3. great look

In the Early Middle Ages, the helmet was a representative object that to some extent represented a crown or headband. A large number of the presented helmets are decorated and the suspension mechanisms were understood as options for decorating the helmet – we can mention type 3 as a whole. We can mention that subtype 3.4 appears in four material variants: iron, copper alloy, gold-plated copper alloy and silver. In addition, we must add that the laborious mail suspension methods carried the message of the owner’s wealth.

A note to distribution

While defining the subtypes, I noticed that while some are geographically indifferent (eg 1.1 and 1.2) and appear throughout the defined area, others are more regionally specific. The same conclusion emerged from interviews with Adam Kubik and Artem Papakin, who also believe that some methods of mail suspension are typical for some regions. Based on the finds listed above, I tried to include some groups on the map, which brought interesting results.

Distribution of subtypes 2.2 and 3.3 (green), 2.3 and 3.5 (orange), 3.4 (blue).

The group of subtypes 2.2 and 3.3 has its focus in Central and Eastern Europe, especially in Poland and Ukraine. This group seems to be related to the oldest helmets of the Black Mound type, as evidenced by findings from Manvelovka and Pécs. It seems that these helmets are very close to the helmet from Kazazovo (Krasnodar region), whose shape falls under the type of Stolbišče. This connection seems to be in line with the statement that the Stolbišče type was a precursor to the Black Mound type, which originated in the area of the Khazar Empire (Papakin – Bezkorovajnaja – Prokopenko 2017).

The group of subtypes 2.3 and 3.5 has been used in the long belt from Siberia through the southern Urals to the Ryazan region and further south in the Krasnodar region and Georgia, for about 600 years. It is certainly interesting that the three oldest helmets (Turajevo, Tsaritsyno, Petra) belong to the late Roman helmets. The highest frequency of helmets from this group can be found in the southern Urals and in the Krasnodar region. The helmets of this group do not occur west of the Don.

Subtype 3.4 occurs in Central, Northern, Western and Eastern Europe. Kulešov (2017: 547) has already pointed out that this method is a European feature that is not found in the Middle East or Central Asia. The map shows that the helmets of this subtype do not extend east of the Dnieper.

These findings may be of interest not only to reenactors but also to academics in determining the geographical origin of new helmet pieces and fragments.

Acknowledgment

At this point, I would like to thank my mentor Sergei Kainov, who aroused my interest in the topic years ago. My heartfelt thanks go to Tomáš Cajthaml, who was involved in the production of graphics. No less credit for the creation of the article belongs to Aleksandra Ščedrina, who provided me with unpublished literature. I also thank Artem Papakin and Adam Kubik for the consultation. Last but not least, Michal Bazovský, Jan Seman and Jan Zbránek, who sent me photos of their helmets, also deserve my gratitude, as do the craftsmen and sellers of helmets, who have recently bombarded me with messages, on the initiative of which I decided to write my work.

Here we will finish this article. Thank you for your time and we look forward to any feedback. If you want to learn more and support my work, please, fund my project on Patreon or Paypal.

Bibliography

Arendt, Wsewolod (1936). Der Nomadenhelm des Frühen Mittelalters in Osteuropa. In: Zeitschrift für Historische Waffen- und Kostümkunde, 26–34.

Arwidsson, Greta (1942). Valsgärde 6, Uppsala.

Arwidsson, Greta (1954). Valsgärde 8, Uppsala.

Arwidsson, Greta (1977). Valsgärde 7, Uppsala.

Beard, C. R. (1922). Ein Helm des 11. Jahrhunderts vom Schlachtfeld zu Walric. In: Zeitschrift für Historische Waffen- und Kostümkunde, B. 9, H. 6/7, Dresden, 217.

Bernart, Miloš (2010). Raně středověké přílby, zbroje a štíty z Českých zemí, Praha: Univerzita Karlova.

Bobrov 2013 = Бобров Л. А. (2013). Киданьский шлем из Забайкальского краеведческого музея // Военное дело средневековых народов Южной Сибири и Центральной Азии, Новосибирск, 75-79.

Bocheński, Zbigniew (1930). Polskie szyszaki wczesnośredniowieczne, Kraków.

Bravermanová, M. – Havlínová, A. – Ledvina, P. – Perlík, D. (2019). Nová zjištění o přilbě a zbroji zv. svatováclavské. In: Archeologie ve středních Čechách 23, 235–310.

Brooklyn museum (2020). Helmet 37.1600E. In: brooklynmuseum.org [online]. [2020-07-22]. Available at: https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/118125

Caple, Chris (2020). The Yarm Helmet. In: Medieval Archaeology, 64:1, 31-64.

Čurilova 1986 = Чурилова, Л. Н. (1986). Погребение с серебряной маской у села Манвеловки на Днепропетровщине // СА 1986, № 4, 262–263.

D’Amato, Raffaele (2015). Old and new evidence on the East-Roman helmets from the 9th to the 12th centuries. In: Acta Militaria Mediaevalia XI, Kraków – Sanok – Wrocław, 27-157.

D’Amato, R. – Spasić-Đurić, D. L. (2018). The Phrygian helmet in Byzantium: archaeology and iconography in the light of recent finds from Braničevo. In: Acta Militaria Mediaevalia XIV, Kraków – Sanok – Wrocław, 29-67.

Ehlton, Fredrik (2003). Ringväv från Birkas garnison, Stockholm. Available at: http://www.erikds.com/pdf/tmrs_pdf_19.pdf.

Geßler, E. A. (1929). Der Helm von Chamoson (Kanton Wallis). In: 37. Jahresbericht des Schweizerischen Landesmuseums, Winterthur.

Graham-Campbell, James (1980). Viking Artefacts: A Select Catalogue, London.

Grieg, Sigurd (1947). Gjermundbufunnet : en høvdingegrav fra 900-årene fra Ringerike, Oslo.

Hejdová, Dagmar (1964). Přilba zvaná „svatováclavská“. In: Sborník Národního muzea v Praze, A 18, no. 1–2, 1–106.

Hensel, Witold (1987). Słowiańszczyzna wczesnośredniowieczna. Zarys kultury materialnej, Warszawa.

James, Simon (1986). Evidence from Dura-Europos for the origin of Late Roman helmets. In. Syria 63, 107-134.

Kainov, S. Y. (2017). The Helmet from Krasnodar Territory. In: Maksymiuk, K. – Karamian, G. (eds). Crowns, hats, turbans and helmets The headgear in Iranian history volume I: Pre-Islamic Period, Siedlce-Tehran, 255-261.

Kainov 2019 = Каинов, Сергей Юрьевич (2019). Сложение комплекса вооружения Древней Руси X – начала XI в. (по материалам Гнёздовского некрополя и поселения). Диссертация на соискание ученой степени кандидата исторических наук Том I, Москва.

Kainov – Kamenskij 2013 = Каинов С.Ю. – Каменский А.Н. (2013). О неизвестной находке фрагмента шлема с Дубошина раскопа в Великом Новгороде // Новгород и Новгородская земля. История и археология. Вып. 27, Великий Новгород, 179-189.

Kainov – Menšikov – Rukavišnikova 2020 = Каинов, С. Ю. – Меньшиков, М. Ю. – Рукавишникова, И. В. (2020). Шлем из комплекса 3 могильника у хутора им. Карла Маркса // Древние памятники, культуры и прогресс. A caelo usque ad centrum. A potentia ad actum. Ad honores, М., 200-211.

Kirpičnikov 1971 = Кирпичников А. Н. (1971). Древнерусское оружие: Вып. 3. Доспех, комплекс боевых средств IX—XIII вв., АН СССР, Москва.

Kirpičnikov 2009 = Кирпичников А. Н. (2009). Раннесредневековые золоченые шлемы, СПб.

Kubik, A. L. (2016). Introduction to studies on late Sasanian protective armour. The Yarysh-Mardy helmet. In: Historia I Świat 5, Siedlce, 77-105.

Kubik, A. L. (2017). Mysterious helmet from Verden and its “link” with Tibetan helmets. In: Historia I Świat 6, Siedlce, 133-139.

Kubik – Radjuš (2019). = Kубик, А. Л. – Радюш, O. A. (2019). Шлемы многосегментной конструкции у восточных врагов поздней Римской империи: находки из Царицыно (Рязанская обл.) и их место в оружиеведческом дискурсе // Лесная и лесостепная зоны восточной Европы в эпохи римских влияний и великого переселения народов, Конференция 4. Часть 2, Тула, 84-102.

Kulešov 2017 = Кулешов, Ю.А. (2017). Об одной серии ранних золотоордынских шлемов из музейных коллекций Украины и Болгарии // Добруджа. № 32: Сборник в чест на 60 години проф. д.и.н. Георги Атанасов, Силистра, 537-558.

Lindqvist, Sune (1931). En hjälm från Valsgärde, Uppsala.

Lindqvist, Sune (1950). Vendelhjälmarna i ny rekonstruktion. In: Fornvännen 45, 1–24.

Mažitov 1981 = Мажитов, Н.А. (1981). Курганы Южного Урала VIII-XII вв., М.

Meadows, Ian (1996–7). The Pioneer Helmet. In: Northamptonshire Archaeology 27, 191–3.

Michalak, Arkadiusz – Glinianowicz, Marcin (2013). Rediscovering Bernard Engel’s helmet. In: Waffen- und Kostümkunde 55/1, 31-46.

Nagy, Erzsébet (2000). A pécsi sisak. In: Pécsi szemle 3, 2-3.

Nerman, Birger (1969). Die Vendelzeit Gotlands II. Tafeln, Stockholm.

Ožeredov 1987 = Ожередов, Ю.И. (1987). Старицинские находки // Военное дело древнего населения Северной Азии, Новосибирск, 114-119.

Papakin – Bezkorovajnaja – Prokopenko 2017 = Папакін, А. – Безкоровайна, Ю. – Прокопенко, В. (2017). Шоломи типу «Чорна Могила»: нові знахідки та проблема походження // Науковий вісник Національного музею історії України. Зб. наук. праць. Випуск 2 / Відп. ред. Б. К. Патриляк. – К., Левада, 45–56.

Paulsen, Peter (1967). Alamannische Adelsgräber von Niederstotzingen (Kreis Heidenheim), Stuttgart.

Plavinski 2013 = Плавінскі, Мікалай (2013). Узбраенне беларускіх земляў Х–ХІІІ стагоддзяў, Мінск.

Poklewska-Koziełł, Magdalena – Sikora, Mateusz (2018). Szyszak z Giecza — szczegółowa inwentaryzacja obiektu i stan badań / Helmet (szyszak) from Giecz. A Detailed Inventory and the State of Research. In: Sankiewicz, P. – Wyrwa, A. M. (eds). Broń drzewcowa i uzbrojenie ochronne z Ostrowa Lednickiego, Giecza i Grzybowa, Lednica, 109-122.

Rabovyanov, Deyan – Dimitrov, Stanimir (2017). Western European armour from medieval Bulgaria (12th-15th centuries). In: Acta Militaria Mediaevalia XIII, Kraków – Sanok – Wrocław, 37-53.

Radjuš 2019 = Радюш, O. A. (2019). Престижное вооружение и доспех V – нач. VI вв. на востоке раннеславянского мира // Балкан, Подунавље и Источна Европа у римско добе и у раном средњем веку, Нови Сад, 261–288.

Rychter, M. R. – Strzyż, Piotr (2016). A forgotten helmet from Silniczka in Poland. In: Fasciculi Archaeologiae Historicae 29, 105-113.

Samokvasov 1916 = Самоквасов, Д. Я. (1916). Могильные древности Северянской Черниговщины, Москва.

Sankiewicz, Paweł (2018). Hełm stożkowy z jeziora Lednica / A Conical Helmet from Lake Lednica. In: Sankiewicz, P. – Wyrwa, A. M. (eds). Broń drzewcowa i uzbrojenie ochronne z Ostrowa Lednickiego, Giecza i Grzybowa, Lednica, 123-132.

Sizov 1902 = Сизов, В. И. (1902). Курганы Смоленской губернии I. Гнездовский могильник близ Смоленска. Материалы по археологии России 28, Санкт-Петербург.

Shchedrina, A. Y. – Kainov, S. Y. (v tisku). Helmet from the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina. In: Acta Militaria Mediaevalia XVI, Kraków – Sanok – Wrocław.

Schneider, Hugo (1967). Des Helm von Niederrealta: Ein neuer mittelalterlicher Helmfund in der Schweiz. In: Waffen- and Kostumkunde 9/2, München, 77-90.

Sjösvärd, L. – Vretemark, M. – Gustavson, H. (1983). A Vendel warrior from Vallentuna. In: J. P. Lamm – H. Ä. Nordström (eds.). Vendel Period Studies. Transactions of the Boat-Grave Symposium in Stockholm, February 2–3, 1981, Stockholm, 133–150.

Skvorcov 2014 = Скворцов, К. Н. (2014). Средневековый шлем из могильника Кляйнхайде // Краткие сообщения Института археологии АН СССР, Вып. 232, М., 203-213.

Slanov 2007 = Сланов, А. А. (2007). Военное дело алан I – XV вв., Владикавказ.

Solovjev 1987 = Соловьев, А.И. (1987). Военное дело коренного населения Западной Сибири: Эпоха средневековья, Новосибирск.

Stolpe, Hjalmar (1912). Graffältet vid Vendel, Stockholm.

Tweddle, Dominic (ed.) (1992). The Anglian Helmet from 16-22 Coppergate, The Archaeology of York. The Small Finds AY 17/8, York.

Vike, Vegard (2000). Ring weave : A metallographical analysis of ring mail material at the Oldsaksamlingen in Oslo, Oslo. Available at: http://folk.uio.no/vegardav/brynje/Ring_Weave_Vegard_Vike_2000_(translated_Ny_Bj%C3%B6rn_Gustafsson).pdf.

Vlasatý , Tomáš (2015a). Další fragment přilby z Birky. In: Projekt Forlǫg: Reenactment a věda [online]. [2020-07-22]. Available at: https://sagy.vikingove.cz/dalsi-fragment-prilby-z-birky/

Vlasatý , Tomáš (2015b). „Grafnir hjálmar“. Komentář k vikinským přilbám, jejich vývoji a používání . In: Projekt Forlǫg: Reenactment a věda [online]. [2020-07-22]. Dostupné z: https://sagy.vikingove.cz/vikinske-prilby/

Vlasatý , Tomáš (2016). The helmet from Gjermundbu. In: Projekt Forlǫg: Reenactment a věda [online]. [2020-07-22]. Available at: https://sagy.vikingove.cz/the-helmet-from-gjermundbu/

Vlasatý , Tomáš (2018a). The Helmet from Bojná (?), Slovakia. One of the biggest mysteries of Slovakian Early Medieval archaeology. In: Projekt Forlǫg: Reenactment a věda [online]. [2020-07-22]. Dostupné z: https://sagy.vikingove.cz/the-helmet-from-bojna/

Vlasatý , Tomáš (2018b). Ozdobné lemy kroužkových zbrojí. In: Projekt Forlǫg: Reenactment a věda [online]. [2020-07-22]. Available at: https://sagy.vikingove.cz/ozdobne-lemy-krouzkovych-zbroji/

Vlasatý, Tomáš (2020). Přilby typu „Černá mohyla“ : nové nálezy a problém původu. In: Projekt Forlǫg: Reenactment a věda [online]. [2020-07-22]. Available at: https://sagy.vikingove.cz/prilby-typu-cerna-mohyla/

Volkaitė-Kulikauskienė, Regina (1965). Ankstyviausių šalmų Lietuvoje klausimu. In: Lietuvos TSR mokslų akademijos darbai. A serija, V., nr. 2(19), 59–71.

Wierzbowski, Dobrosław (2016). Awarski (?) hełm i grot włóczni z Verden. In: De Re Militari nr. 1-2016 (3), 21-29

Wilbrand, W. A. J. (1914). Ein frühmittelalterlicher Spangenhelm. In: Zeitschrift für Historische Waffenkunde 6, 48-50.